BIRTH, DEATH, DREAMING AND DISRUPTOIN: LETS SPREAD OUR ARMS WIDE TO CATCH THEM ALL

Human and more-than-human ecologies, speculative fiction and contemporary art blend, meld and merge in this conversation between Rhona Eve Clews (RC) and Stephanie Moran (SM).

Stephanie Moran is an Associate Partner at Etic Lab and a PhD student with Transtechnology Research, Plymouth. She is researching nonhuman diegetic sensory worlds and ecological aesthetics. At Etic Lab she is leading on a project in collaboration with Artist Maggie Roberts and an octopus to produce an octopoid AI.

Rhona: Stephanie and myself met in 2018, whilst I was a student at Slade School of Fine Art, visiting the library of Iniva on a tour with artist Joy Gregory, where Stephanie was Library Manager at the time. We then met spontaneously again in 2019 via a CHASE series of PhD seminars on science fiction and ecology, organised between Goldsmiths and Birkbeck. With a desire to acknowledge the variety and breadth of ideas discussed in this issue I compared the sensation of trying to catch jellyfish, needing to spread our arms wide to catch them all.

RC: Hi Stephanie! As a way into SF, contemporary art and this issue’s contributions, I'm thinking about the role of dreaming. You astutely recognised the theme of disruption in the works; of birth and death, and I added transformation, after I had initially considered adaptation, and now, I feel most seduced by dreaming.

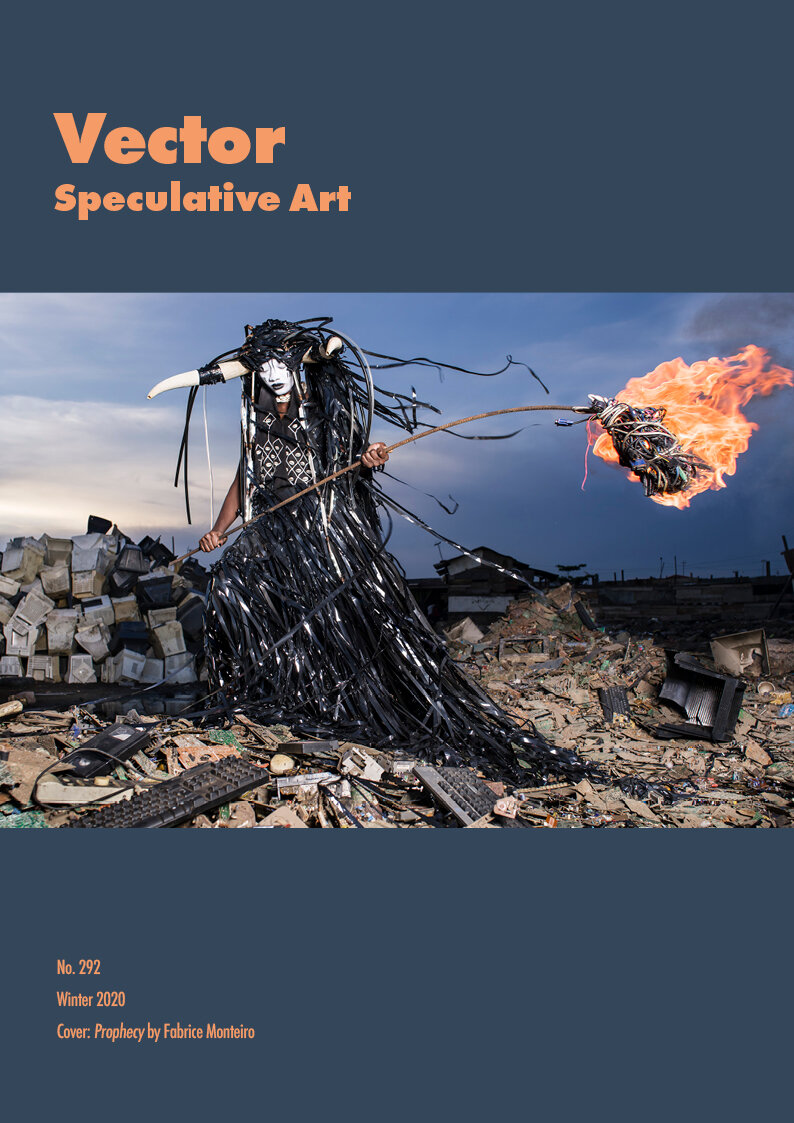

Vector, Speculative Art, Issue 292, Fall 2020 cover

Dreaming as a space for processing/digesting/transforming, allowing things to die, and then also a space for conjuring — for allowing new worlds, possibilities and visions to emerge. Dreaming as a bridge space. Dreaming and its relationship with reality too. How you cannot tell you are in a dream until afterwards. It’s immersive, like air and water. Or as Sissel Marie Tonn from Sensory Cartographies describes a landscape in this issue: “You’re either inside a cloud, or outside a cloud.” This feels both artistic and science-fictional in itself. And then I am thinking about how this sits with birth, death and disruption?

Hydrogen, Oxygen and that slippery stuff (Water), Still, Rhona Eve Clews, 2019

SM: Mmm, I like these connections to dreaming. Juliana Huxtable talks about dreams and epigenetics in her interview. And in Smin's article, ‘Fashion and SF,’ the two narrative strategies from Dan Hassler-Forest's theory that encourage worlding are "a lack of narrative closure, and the process of immersion," both of which are dream conditions. The liminality of dream-space is inevitably also a condition of birth, death and transformation. Perhaps the disruptive potential of art and SF is linked to dreaming?

RC: Yes, I think this immersive quality of dreams is often embodied through scale and vision in SF and art. Whole worlds, space operas, civilisations and currencies are born, function and dysfunction here. Via imagination, we are offered glimpses into other realities outside of the normative and mundane. SF and art potentially embody a willingness to confront the status quo and challenge what does not match up to an overarching potential. It takes guts to voice what isn’t working, and SF and art both have that capacity for progressive leadership. Juliana Huxtable addresses this directly in her interview when discussing gender. SF and art are able to envisage and hold a sense of the alternate or possible, whereas so many attempts at change, even those that are seemingly about innovation or improvement so often default to the existing social norms for fear of disruption, ending up settling for staying stuck.

Felt sense iii (near the lighthouse), 35mm slide, installation documentation from Envisioning other worlds, RAW Labs/ Lumen, Bow Arts, Rhona Eve Clews, 2019

SM: Well yes, thinking systemic change on a scale of constructing new worlds is what SF and art are good at; to disrupt the cybernetic governing code of a system, which I talked about in my article; the conserving of the status quo which in the case of e.g. the economy, means the status quo of power and distribution.

RC: And of Man1, as you discussed in your talk at Iniva.

SM: Yes, Sylvia Wynter's concept of Man1, Man2 and Man3, that represent a consecutive series of 'human governing master codes' beginning in the seventeenth century in the West. Wynter uses a cybernetic approach to history, showing how this series of transformations actually function to maintain relations of power. Each is constructed on top of compressed strata of embedded hierarchical forms and inequalities necessary for the system to operate. This is expressed in many of these essays' discussion of colonialism, for example, something SF has a foundational relationship with. These systems are cybernetic in the sense that they automatically adjust to maintain a status quo. And like you say, SF and art are invested in different kinds of transformation altogether. They seek to imagine and dream truly new and different worlds.

Alien Ontology avatar, Stephanie Moran, 2018

RC: Yes, absolutely. The colonial vision seems to assume an unending state of dominant certainty and control which is a deeply flawed and violent fantasy! Perhaps Sensory Cartographies’ perspective that nature is impossible to categorise as it is ‘a constantly developing mass of life’ is helpful here? Alex Buckley’s article on African Contemporary artists and SF centre-stages artists considering alternate realities, such as Nuotama Frances Bodomo who envisages an alternate history where the Zambian space project really did send a young woman to space, whereas in this current reality, the project never received sufficient funding. Dreaming possibilities enables us to experience a potential without them having needed to take place.

SM: Thinking about the process of change and adaptation and mimicry, and maybe even more so, hybridity. Alex Buckley also talks about hybridity and synthesis: particularly in the work of Beninese-French artist Emos de Medeiros, who fuses sci-fi, space travel and technology with Beninese traditional cultural forms, philosophy and divination. Buckley’s discussion of Africanfuturist and Afrofuturist artists as a whole emphasises hybridity in Black technofuturisms. I think mimicry and hybridity are things you are doing in your work. I love the eating/becoming theme in your work. The way that we can connect to stuff through eating it, and then in some way you become that thing. Eating the earth (Humic densities (Earth)) and the water (Hydrogen, Oxygen and that slippery stuff (Water)) where you are talking about swimming in the ponds, I thought that was really beautiful in terms of thinking how we become other things.

Humic densities (Earth), performance at you’re mulchy green, you’re verdant matter, Slade School of Fine Art, Rhona Eve Clews, 2019

SM: And I suppose that you are talking about bodily, somatic interconnectedness and that links with hybridity and symbiogenesis. I found something today which was really key. A quote from Lynne Margulis’ book, Symbiotic Planet, saying that she believes that “most evolutionary novelty arose and still arises directly from symbiosis.” I believe that that is the case. You can think about evolution in cultural terms just as much as biological terms. We change through copying stuff and synthesising stuff. And this is what SF and art push. You work with stuff that's known and then combine it in different ways.

RC: I completely agree, especially considering the vital role mimicry plays in growth and learning. We learn to do things by mimicking. It’s fundamental in moving from childhood to adulthood. It also acknowledges the inevitable lack of neutrality there is in perceiving and experiencing, and I noticed Sensory Cartographies’ interrogating assumptions about the neutral gaze too. Mimicry also makes me think about Fiona Moore’s interview with Hod Lipson, how AI is framed as a child intermittently in their conversation: “where robots might be raised like children.”

Still from Private life of plants, BBC, 1995

SM: I’m really interested in what Lipson has to say about AI creativity, and the possibility of less dystopian AI futures, including AI with their own culture and art. In my work at tech consultancy Etic Lab, we’ve observed and written about the increasing autonomy of creative AI, and the ways it is affecting human culture.

RC: The relationship of AI and culture is so multi-layered, and I’d love to talk with you more about what you’re discovering in terms of autonomy. Advances in AI are fascinating partly because they ask us to reflect on the very nature of consciousness and human intelligence. Similarly, it’s increasingly recognised that SF operates as a lens through which we can observe our current status quo, norms etc., and the potential sociological and philosophical aid this might offer, refreshing our perspective from observing ourselves. Dan Byrne-Smith’s introduction to Science Fiction, his recent anthology on SF and contemporary art, frames both as sketchbooks with agency: "The kind of stories that can be told in the field can often be understood as not only reflections of the spaces of culture in which they operate, but also forces in themselves that shape those spaces [...] with this recognition comes the possibility of imagining both science fiction and science-fictional thought as having a power to influence possible futures. Images of alien worlds on screen could show strange ecologies with the potential to sensitise viewers to non-human life on their own planet."

Science Fiction, Documents of Contemporary Art, Whitechapel, Edited by Dan Byrne-Smith, 2020

RC: I also feel that much of the transformative agency of science fiction is connected with its potent, dreamlike, consciousness-esque qualities. Juliana Huxtable mentions this in her interview when she talks about parties and nightlife. The idea that who she is on the way to the party is different to the person at the party. I noticed this as a teenager, where I would dress in a certain way, then walk down the same stretch of road in different clothes, and get a different reaction. I didn’t like this at the time, but I can see the freedom in it now. I have had dreams where I have observed myself from a different reality / age / location, or perspective, and such temporary states have hung around and enabled new behaviours upon waking. For me it connects to Rupert Sheldrake’s writings on the morphic field. Although Juliana speaks of an ‘untethered self’ and Sheldrake’s speaks of a blueprint, both acknowledge a non-physical potential that we can reach out and interact with. I wonder if this ability to temporarily embody other perceptions begins with dreaming? SF, art and dreams all employ sketchbook methodologies in their practice of ‘drawing things out’ … in both senses.

Declan Lloyd's essay about the painter Neo Rauch has stayed with me in terms of thinking about Dada and Surrealism as science-fictional, in their collapsing of worlds together, their collapsing of temporalities. Dreaming and memory too, highlighting memory and its glimpses too, as largely visual. I am compelled to understand how this intersects and collides with Rachel Hill’s essay about Lawrence Lek.

SM: Yes there’s an expansiveness to the combination of art and SF, from their cross-fertilisation. As Smin says, we read art, referring specifically to fashion, differently, when we view it as science fiction. More generally, reading art through SF and SF through art expands the ideas of both.

RC: Yes, and I imagine the artist Joan Fontcuberta was aware of this when The Science Museum hosted his Stranger than Fiction exhibition of fictionalised anthropological photographs in 2014. As audiences enter the Science Museum their eyes are honed: as if all the works inside are artefacts, specimens, evidence, seducing viewers into approaching the (actually fictionalised) photographs as “real.” Performance has the power to inform and influence our gaze. We can use our bodies and our identities almost like costumes, which I think is something that the sensory wearables of Sensory Cartographies emphasise?

Sensory Cartographies of Madeira, 2016

I find the cross-fertilisation of interdisciplinary artistic practices so appealing as they tend to encourage an exchange between drawing, performance, writing, etc. and propagate dynamic thinking, feelings and behaviours. This is very refreshing compared to the stiffness of divisions between academic departments, such as the separating of art from science.

SM: Dream-space can easily detach from consensus reality, the "destabilising worlds within worlds" that for Rachel Hill defines SF. She focuses on "the navigation of deep space within pockets of deep time" as a defining condition for SF that connects to Lawrence Lek's work and its "temporally palimpsestic, metastable worlds, routed through the estranging poetics of SF." Neo Rauch's work does something similar, but where Lek performs science fictional archaeologies of the future, as Lloyd says in his article, Rauch is working through palimpsests of surreally dream-like histories and alternate futures visible in the present.

RC: I respond to what you are saying here about layers and ruins. In Lloyd’s essay he also discusses writer William Burroughs’s cut-up method in relationship with Rauch and there is a sense of the painter employing a similar method of pulling upon different temporalities to birth new landscapes. Juxtapositions which might, in theory, seem jarring, somehow, through the fictioning process of painting, appear to make sense and the edges between worlds are able to soften. Lloyd goes on to compare artists Giorgio de Chirico and Rauch and I think both are able to channel dream-like scenes and atmospheres through their image-making. Different realms sit astride and amongst one another, and as the viewer, we are potentially able to enter such spaces and experience our own reconfiguration.

Jackfish hitching a ride inside a jellyfish, Fabien Michenet, 2019

SM: Yes this connects with what I was thinking about birth. Also, the ecological and decolonial concerns discussed in Andrew Butler’s review article, particularly artist Denenge Akpem, who “transforms herself into a hybrid human-jellyfish, with lighted fibre-optic tentacles,” and Ellen Gallagher’s Ichthyosaurus installation at the Freud Museum, while Afrofuturist writer Nnedi Okorafor’s Lagoon is mentioned in connection with decolonial ecological artist Ama Josephine Budge. Going back to hybridity…

RC: I feel this artistic desire of becoming and blending with another feels dream-like in its ability to occupy another embodiment/perception. It feels like a joyous and persistent theme in this issue: the character in Juliana’s novel consuming colloidal silver and bat-gene orange juice to become “a kind of midnight-blue bat-like person”; Sissel Marie Tonn’s work on “becoming a sentinel species”; Jonathan Reus’ desire to meld minds with his computer using electromagnetic pick-up coils, never mind his desire to channel his inner seagull! Alex Buckley also highlights Emos de Madeiros’ ‘Vodanaut’ series merging the organic and inorganic, combining cowry shells with smartphones. And I know there’s more! In the work of mine you refer to, Hydrogen, Oxygen and that slippery stuff (Water), I am recalling a kind of experiential fantasy of temporarily transcending my human body and blurring, via water, into other bodies, such as the Hampstead Women’s Pond. Your work with freshwater mussels also comes to mind, and Sylvia Wynter’s research in terms of Man1 and Man2. How perception gets normalised and is typically assumed to be that of an individual, human, brain-based consciousness, rather than in collective, bodily or non-human experience. There is a great capacity for birth in hybridity. I am in agreement with Sensory Cartographies’ perspective that a “violent normalisation of bodies” occurs when we narrow and over-simplify the range of senses available to us, and I am compelled to instead consider the vital notion that “sense is highly plastic.”

Back cover of Vector Speculative Art featuring image, Untitled, Juliana Huxtable, 2019

SM: I’m aware that birth, death and transformation (and their analogues, worlding-fictioning, collapse-degrowth-ruin, metamorphosis) are not separate things or linear progressions, they interweave and are exchangeable when viewed from different perspectives, like the ideas in this issue. Hill's essay on Lawrence Lek's creation of virtual worlds, for example, while seeming to fit neatly within worlding, is complicated by their construction on top of and within the ruins of previous (contemporary) worlds, and the simultaneous transformation of these; while Alex Butterworth's essay on Damien Hirst's exhibition Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable discusses the fictional world fabricated by Hirst that would appear to be a clear-cut case of fictioning, while the shipwrecked content of that fictional world represents both a collapse and a transformation of the objects into relics or future archaeology, depending on your viewpoint.

Worlding and fictioning, like gods, rely on belief, or at least the willed suspension of disbelief: the creation of worlds is a collective act of agreement to perceive the same thing, or to perceive enough of the same thing that it reaches substantiality (an agreed area of overlap in perception, if you like). This idea is explored in Butterworth's essay. Butterworth uses another world, that of the social media platform Twitter, to test the reality status of Hirst's world; effectively suggesting that it 'exists' as part of the larger fiction that constitutes the art world.

RC: Yes, there is a conscious/unconscious ‘buying-into’ here. In dreams, in art, and in SF, things make their own mesmeric kind of sense, a kind of sense that doesn’t operate in conventional consensual reality. Sensory Cartographies mention this with regard to tactile maps and the physical acknowledgement of space as a subjective experience. Reflecting on consensual and non-consensual realities conjures some shamanic training I did, alongside my early experiences with drugs! Approaching this Vector issue I was aware that “SF and art” as less of an established canon doesn’t (thankfully!) yet have a reductive set of ‘three main artists’ that people default to. However, in such a void I realise the old address that I would return to would then be that of psychedelic and drug-induced art. It feels rather cliched and there’s the non-consensual reality again! I suspect art and science fiction are the spaces where the science-loving go, to escape the science world’s demand for consensual reality!

SM: As Frank Cioffi points out in his article, conceptual art and SF's use of objects, object / nonhuman perspectives, realism, and the non-mimetic thing-in-itself, exposes ways the human sensorium might not be adequate to record the totality of the “real.” Cioffi draws analogies between the limits of human perception and the invisibility inherent to conceptual art practices, such as Agnes Denes and her Human Dust project.

RC: Yes Agnes Denes’ scenes feel dream-like too, I don’t know about anyone else, but when I first saw that wheatfield in the city (Wheatfield - A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan, 1982) I almost recognised it as a still from a dream or a film somehow. Certain images have the ability to resonate and reverberate like that, and I think both SF and art can capitalise upon this awareness, using dreaming to shape and inform the worlds we are building in our wakeful state.

Great talking with you Stephanie!

-

I would like to extend thanks to Editors Jo Lindsay Walton and Polina Levontin for permission to reproduce the piece here, to Stephanie Moran for the lively conversation and to all the contributors for creating such a wide-reaching and exciting text! You can see more and purchase a complete physical copy here.